Summary

« Migration ». An ubiquitous term in political, legal, economic and environmental news. What does the media sphere mean? What migration flows are we dealing with? Nowadays, many researchers prefer to speak of « mobility » or « circulation », the terms being more explicit to understand fluxes with variable geography in time. « Migrants ». A term that encompasses all types of citizens in a context of traffic, caused by wars, the environment, the economy – refugee citizens, applicants for international protection, climate displaced, cross-border workers, brain drain pensioned exiled or even taxpayers… Among all these types of profiles, one thing in common: the search for a better life. In this quest, we can observe some positive constants over the course of history such as host country stability or the wealth of socio-cultural exchanges. However, the recurrence of discourse of rejection remains dominant. Over time, we can see the stakes of deontological information regarding the representations of displaced populations (invaders, criminals, rapists, etc.). These are media representations of « migration » which we will deal with in the prism of the most stigmatizing news items, the most denunciatory cartoons, from the Old Regime to the present day, in the Mediterranean basin.

Keywords: e / im / migration, history, press, stigmas, caricatures / Article FR

Media projections around « migrants » – Searching well-being or to face a rejection?

Among all the regions of the world, the Mediterranean basin is a remarkable observatory: from Egypt to ancient Greece, through the period of the Crusades, the Ottoman Empire, or the 19th-century working class up to the present day, mass migrations have been renewed. These flows thus contribute to the construction of new spaces. Despite the variety of historical contexts and disruptions, it is possible to detect a number of continuities, recurring images, in the narrative of migration phenomena. If we look at the media representations of these continuities, we must at least go back to the 19th century with the emergence of courtroom press under the Ancien Régime. In those times of intra-mural and then cross-border migrations, news reports relied on accounts that tended to violently stigmatize all migrants. Nowadays, this kind of stigmatization is renewed and intensified with the digitalization of information. To illustrate these media coverages, we will draw on works from intersecting disciplines between History (Vigarello, Noiriel, Gastaut, Kalifa), Information and Communication Sciences (Bonnafous), and the interdisciplinary network MIMED (Migrations in the Mediterranean). We will thus focus on the media perceptions of the 19th and 20th centuries before concentrating on the reception of information on current circulation flows in the Mediterranean, through the cartoons of press cartoonist Ali Dilem. Finally, we will advocate for more ethical information concerning the quest for well-being and the risk of rejection that the so-called « contemporary migrant » will face.

The rural migrant in the press of the Ancien Régime

From the Latin « migratio, » derived from the verb « migrare, » the term « migration » refers to the act of migrating, leaving a place, changing residence, departing, emigrating, etc. Understanding contemporary migration flows also involves considering their complexity throughout history. Populations leave, some only pass through, others shuttle back and forth with their country of origin. However, throughout history, with population movements, newcomers are often blamed.

In France, under the Ancien Régime, the urban world detested rural migrants and the societal changes related to new forms of labor. The image of these immigrants was built on prejudices: they were seen as foreigners invading the space and taking others’ jobs for lower wages. At that time, the work involved service jobs in hotels, restaurants, management, and sales in shops. Rural migrants were thus considered job thieves, taking easier jobs initially reserved for women, as they required less physical effort in those industrial times. Focusing on the media perception of this working class, one will also notice through news reports that, in addition, the rural person, the « pauper, » the « louse-ridden, » was often depicted as guilty of the most abject crimes like rape. These are the same taboo crimes, the dark figures, « grey numbers »1, committed in all other social classes but overrepresented in the media when it comes to rural migrants, making the « lower » social class appear the most criminal and uneducated among the French. Thus, in the early 19th century, public opinion equated aggressors with frustrated monsters from the rural world. As summarized by historian Georges Vigarello, poorly known populations were instantly stigmatized as « barbarians » and guilty (1998: 187):

“Industries, their congestion, the more numerous migrants fascinate and worry. The fear of violence targets less the countryside than the streets, this previously unknown promiscuity in cities […]. The « savages of Paris, » those of George Sand or Eugène Sue, are as many « barbarians living among us, » « tribes » reinforcing the certainty of an increase in crime, workers of a new kind, migrants from the countryside bringing anxiety to the heart of cities.”

With these new unknown populations around the city, the portrayals painted by the press did not necessarily help their integration. The image of this intra-muros migration in the metropolis is noticeable in the French press La Gazette des Tribunaux2. Born in 1825, the newspaper specialized in court reporting, did not escape the trend of sensational news, a lucrative business. At that time, its revamped formula was part of a new press that generated curiosity by addressing all social classes. As Georges Vigarello noted (1998), the daily newspaper thus reflected a new criminal topography when it serially reported, around 1840, the sexual crimes committed by workers, intermixing adult rapes and child rapes: “indecent assaults are frighteningly renewed” (12/10/1838), especially those of “quarry workers” (20/05/1833), “bricklayers” (06/05/1841), “chimney sweeps” (20/06/1833), “charcoal burners” (02/04/1842), “two half-drunk men on a female worker” or on “a young girl returning from a ball” (20/04/1842). Perceived as false individuals, people to be banned, they were associated with places forgotten by progress and depraved. They came from the suburbs – boroughs of the city – and were seen as false and filled with false, uneducated bourgeois, just as the suburbs referred to people « banished from the place, » at least one league away from the city at that time. Press headlines related to these working-class neighborhoods followed: “young men from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine on an underage girl,” or “12 printer workers from the faubourg,” prompting La Gazette to “call for all the severities of justice” (12/10/1838) for acts “repeated several times, always under the same conditions in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine” (01/05/1841)3. One can see that the sensational news revealing social representations operated with a particularly formidable mechanism in the case of immigration: it revealed social unease, but also rejection, a certain xenophobia. The place nourished the stigmas. For the press of that time, violent offenses like thefts and assaults belonged primarily to the world of villages and hamlets. The argument was even systematized since the 18th century, fixed on a conviction: “the incompatibility between the existence of certain crimes and the existence of civilization” and “the association of murder or rape with a rural world made of archaism opposed to an urban world made of modernity” (Vigarello, 1998: 131-133). Progress was measured by urbanity: the city, its development, and its lights should drive away violence and sordidness. Finally, the utopia of an industrial and urban civilization, ready to remedy all the ills of society, slowly took shape: civilization should erase crimes and offenses. It is at the heart of these certainties, however, that questions arise about the reality of violence and the way to evaluate it, the city and crime suggesting previously unknown concerns.

Indeed, speaking of a “world of villages and hamlets,” and comparing it to “places forgotten by progress,” one can see, through press analyses, a “civilization trial” designating French rural migrants as “uncivilized” here, and by simplistic association, opposing them to modernity as supposedly primitive and ignorant (Saadaoui, 2010). These reflections lead to questioning the effects of an urban pathology. The city would rather be a counter-example, a “sticky den of corruption, a chasm of temptations” whose congestion would exacerbate all dangers just as the increase in crimes and offenses would only signify a growth in “urban turpitudes and depravities” (Vigarello, 1998: 136).

Additionally, demographic studies such as those by Jean-Claude Chesnais (1981) align with the aforementioned historical observations. They examine the perception of these ever-present new migrants, who are now migrant couples, grouped families, and not single men arriving in the city. While the figure of the barbaric murderer is still part of the crime imagination, the press then informs about a threat that becomes more precise, more localized: it is the fear of the neighboring migrant that replaces the fear of the rural dweller, the border migrant – even if urban – being even more « foreign » than the rural French: the Italian and the Belgian first.

« Civilization trial » of the cross-border economic migrant

Up to today, one can see a slow « civilization trial » (Saadaoui, 2010: 17) repeating in these historical reproaches, stemming from Norbert Elias’s work on the processes of civilization (1969), which posits that the « civilized » society, the « court society, » assumes the duty of civilizing other social classes in its own image. With this civilization trial, a new urban sensitivity emerges: « a city feared, revered, and hated where the moral and sanitary norms of the 19th century are born » (Vigarello, 1998: 186), such as the behavioral norms confirming the « emergence of another France » mentioned by historian Yves Lequin (1983: 193). Received ideas are entrenched, notably the one that foreigners are a burden on society and a threat to national cohesion. It is difficult to counter these preconceived notions about migrants without considering a political context that is either favorable or resistant to immigration.

From a rather media-political perspective, prejudices against immigrants from Africa, Latin America, or Eastern Europe increase with the rise of extremism. If we return to the Ancien Régime in France, as explained by Georges Vigarello, we see that the reports in La Gazette des tribunaux (27/02/1887) portray the perpetrators of rapes or gang rapes committed by « foreign » accused individuals: « the Italian subject, an ignoble character, » « Belgian subjects » depicted as « ignorant » or « brutish, » driven by « perverse passions, » frequently make headlines with reductive labels. La Gazette thus creates a « culture of crime, » which increases its national audience, which had long remained modest in its beginnings. Historian Dominique Kalifa (1995: 121) reinforces these observations by discussing the press of the time, which tends to reveal more violent confrontations when they are committed by foreigners, especially if they are brawls after drinking, among workers, between French and Italians, and also among Italians. Such stereotypes often targeted foreigners who joined the lower social classes, equated by the press with « barbarians, » uncivilized people, and new « dangerous classes. » As historian Gérard Noiriel (1988: 249) explains, at the end of the 19th century, while it is true that Italians and Belgians were victims of intense xenophobia, especially in the working world, it must also be noted that the three modern French economic crises (at the end of the 19th century, and in the 20th century during the 1930s and from the mid-1970s) sparked waves of xenophobia against new migrants coming to work. It is clear that the young French working class frightens people, and it is no longer the rural or « migrant » foreigners from the French borders, but the popular and working classes who play the « role of the threat. » The weight of words must be considered in a discourse that can lead to sensitive controversies, as illustrated by the sensational news discussed in the 19th century. Analyzing the discursive forms representing a particular socio-demographic population is useful for understanding the image of first-generation and then second-generation immigrants in the late 20th-century press. The handling of a controversial subject and the ensuing media discourse must be approached with caution. This is precisely the point highlighted by researcher Simone Bonnafous in her book « L’immigration prise aux mots. Les immigrés dans la presse au tournant des années 80″ (1991). This study examined the virulent attacks against populations from North Africa in a section titled « Far-right: from theory to attack » (1991: 48-62). She notably shows through examples from the press how reports and investigations on sensational news can be organized around narratives describing the horror of crimes and offenses committed by immigrants. These immigrants are also accused by the far-right press of the 1950s, such as Minute, of being the rapists of « our » women. For example, the title of the report from October 5 to 11, 1977: « Victim of fifteen thugs, Brigitte is mutilated forever and yet… the ARAB RAPISTS are FREE. »

Stigmas of the so-called immigrant generations

At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, history repeats itself once again, this time for the generation of children born in France, socio-politically referred to as the « second generation of immigration. » The stigmas persist and renew with the most abject crimes — such as gang rape, which the media-political sphere now calls « tournantes » (gang rapes): a woman is « turned, » like a pornographic recreational activity, akin to a « gang bang. » Once again, this is a process of exploiting the « news item that diverts attention » from the country’s economic woes, as examined during times of mass industrial relocation in the 2010 doctoral thesis in Information and Communication Sciences, « Media Treatments and Interventions Around ‘Tournantes’: From the News Item to the Immigration Question? » (Saadaoui, 2010). This occurs in a context where other discourses intersect, where themes of rising insecurity and xenophobia are prevalent in the debates accompanying the 2002 presidential election campaigns. The targeted news item aimed at a specific population appears as an additional trigger for national « moral panics » — as already discussed for French migrations in the 19th century by Gustave Lebon in his aptly titled work, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895). The lack of education and reference points among the so-called first generation of immigrants has often been a spearhead to explain crimes or offenses committed on the outskirts of the city, generating fears and psychoses. Many media treatments focus on the « children of immigration in disarray » (Le Figaro, 11/05/2002).

In 2002, during the year when the press discussed gang rapes as « tournantes » the most, France 2 allocated 100 minutes of prime-time TV to political personalities invited to reflect on the French social climate, not in relation to the primary socio-economic concerns of the French people, but in relation to the theme of insecurity4. Additionally, the then-Minister of the Interior, Nicolas Sarkozy, announced a firm policy towards the « barbarians »: « When they gang-rape in groups of ten, I call them barbarians committing a crime. It is time to use the right vocabulary, » he said on the television set. With this perspective, it is not surprising to see the extreme right-wing party National Republican Movement’s website unabashedly define « tournantes » as follows:

« Tournante: an ‘initiatory’ gang rape, characteristic of the suburbs and cities under the rule of ethnic gangs […] Although difficult to evaluate due to the victims’ silence fearing reprisals, the number of these heinous crimes, mostly affecting minors, is reportedly on the rise according to all specialists. »

Many extremist and xenophobic parties will appropriate the discourse on « tournantes » to point out civilizational problems among the perpetrators of gang rapes. Other openly Islamophobic websites will soon link gang rapes, immigration, and religion, with the same causes producing the same effects. To reach such statements on the web, it is interesting to observe the semantic shift from the news item to the societal issue through the informative discourse.

Once again, information affecting the « image of the elite France » is less mediated. The trial of Parisian CRS officers jailed for gang rape on foreign prostitutes (Le Figaro and Le Monde, 13/12/2003) or the Lille police officers jailed for gang rape (Le Figaro, 28/05/2002) are more obscured. A trial of abuse of power is somewhat covered, following a hearing report of four police officers in Albi, avoiding Assizes for four peace officers presumed guilty of rapes. Journalist Françoise-Marie Santucci for Libération (03/07/2002) recounted the victim’s drama, Laetitia, a young 19-year-old mother, and the sentence imposed on the perpetrators: a simple suspended sentence for several rapes committed between December 1999 and January 2001. Another journalist, Stéphane Thepot (Le Monde, 04/07/2002), reports a statement from Maître Gaubert, the public prosecutor, not without a striking comparison: « It wasn’t a ‘tournante’ like in the suburbs, but a ‘farandole’, » said Mr. Gaubert, who requested the confirmation of the sentences pronounced. » Through these hearing reports, the protagonists differ from those targeted in the treatment of « tournantes. » In this « farandole affair, » there is a defense pattern for the presumed perpetrators, similar to most presumed perpetrators defending themselves by arguing the victim’s consent and the lack of perception of the severity of their acts.

Beyond borders, still in full economic crisis of industrial relocation, the representations of immigration are similar, with once again, a tarnished image of their descendants. If we look at the francophone border presses, Belgian or Swiss, the immigrant’s son appears just as dangerous. In Belgium, for the daily Le Soir, the fault is attributable to the other, the foreigner, often the « African. » This is evidenced, for example, by the article titled: « Justice – Judicial Backlog. Courts Paralyzed Due to Lack of Police Officers (Le Soir, 18/05/05) »:

« On the side of the 54th correctional chamber, to give the priority that is due to a major gang rape case attributed to a gang of young Africans, the MAF (for African Mafia), few cases were scheduled. »

Sabine Pirolt for the Swiss press L’hebdo (23/11/2007, pp. 76-82) dedicated a dossier to the « Swiss gang rapes » titled: « Gang Rapes: Tomorrow, Your Daughter? » In this writing, the media treatment of rapes committed by foreigners in Switzerland is similar to articles in French or Belgian dailies, with the difference that the targeted immigrant populations or their children are often foreigners from the Balkans. The media treatment in Switzerland and Belgium, for part of the francophone press alone, reveals that there are no ideological borders for the fact that the culture of the country of origin can be stigmatized in the host country. The media relay of rape is once again imposed through the lens of immigration, not only for immigrants but also for their descendants, even if they have evolved in values of equality and fraternity.

In this sense, the media treatment of gang rapes, termed « tournantes » at the beginning of the 21st century, reveals a difficult integration process of migrants in the history of French society rather than a phenomenon of exclusion specific to the present time.

Premises of the Caricature of the « Mediterranean Migrant »

Whether through images (cinema, television, press illustrations) or text (articles, reports, dossiers), it is evident that the major headlines of national and regional daily newspapers and weeklies generously fuel the phenomenon of « moral panic » to its peak. This shows that the dark representations of immigration attributed to a particular population remain a significant subject of study today. For instance, the highly publicized crossings of migrants from Africa to Europe via the Mediterranean have seen journalistic treatments contribute to a climate of panic even during the flow of migration: with pathos, narratives lamenting the plight of « migrants, » and also socio-economic projections that pose threats to the host country.

In terms of caricatures on the crises of migrant crossings in the Mediterranean basin, numerous publications by Dilem, an Algerian press cartoonist5, illustrate the issue with humor that blends cynicism, mockery, irony, sarcasm, and burlesque. Under the title « Migrants – Europe Overwhelmed » (Figure 1), the passengers in an overloaded makeshift boat respond in unison, « Not more than we are » (Liberté, 01/09/2015). Another cartoon shows an overloaded boat at sea with the title « 137,000 migrants have already crossed the Mediterranean in 2015 » (Figure 2), and the passengers remark, « It’s the Afrixit! » (TV5 Monde, 03/07/2015). This refers to the financial concerns of Brexit compared to those of African citizens—from North to South. Many caricatures denounce, in the era of the digital industrial revolution, the living conditions of Africans leaving the continent for better economic opportunities, similar to the political motivations seen in the United Kingdom.

Beyond the migrant crossings, their arrivals are also caricatured. For example, one illustration shows a full boat arriving on a beach where a French policeman is placing a « STOP » sign. A passenger responds, « …And how are you going to win the next World Cup? » (Figure 3 – Liberté, 19/07/2018). This image criticizes the inhumanity faced by an economically selective immigration policy, rather than addressing the ignored humanitarian aid.

Regarding arrivals from Africa, we see two men in the sea raising their arms, with one shouting « Help! » Facing them is a Red Cross worker with a buoy on his arm, responding, « Sorry!… I don’t recognize the Syrian accent! » (Figure 4, Liberté, 12/09/2015). This implies that France seems to be concerned only with Syrian expatriates seeking international protection. In this sense, the hypocrisy of Europe and, subsequently, the NGOs that finance more political than humanitarian measures is depicted. These measures are still self-interested, as illustrated by the European disputes over the significance of operations amidst the increasing number of deaths and disappearances at sea between 2011 and 2015.

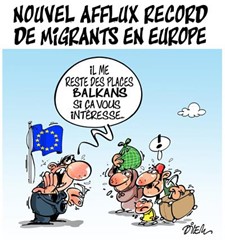

In 2013, the Italian government and its navy initiated Mare Nostrum, sea rescue operations, but this measure was replaced at the end of 2014 by Triton, a European security operation – not a humanitarian one – aimed at deterring citizens departing from Africa. This desire to repel was particularly evident through financial aid and training provided outside the Schengen Area to destabilized countries such as Libya6. Even when immigration appears to be legal with migration flows, it still seems unwelcome, with arguments suggesting that a family of migrants from North Africa would be directed to the Balkans rather than to another part of Europe, implicitly an « Europe of the Six »7. Thus, countries like Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Romania, and Slovenia, now members of the European Union, seem equally depreciated and rejected, as illustrated (figure 5). In short, a second-rate Europe, cheaper and more accessible, like football tickets for national teams sold on the black market outside stadium entrances (TV5, 26/10/2015).

A notable caricature by Dilem is entitled “Family reunification in the Mediterranean” (figure 6, Liberté, 04/19/2015). We can see a mother and three children, joining the drowned father in the depths of the sea, lying on his stomach in the middle of living fauna and flora, fish, shells, starfish, algae… The bubble of fish » ?! » can translate a form of candid questioning, about these improbable arrivals in their environment. The drawing was published on the LICRA8 Facebook page, leading to numerous derogatory messages, which forced it to remove the drawing. For the French weekly Courrier de l’Atlas, journalist Nadir Dendoune was particularly interested in this caricature and its feedback in 2015. For the journalist, via social media, many Internet users were outraged at “a variable geometry of freedom of expression that is regularly singled out.” He cites in particular Sadia, a Senegalese living in Paris who testifies to this burden of “double standards” that he feels: “We can laugh at everything but not with everyone but the problem is that everyone laughs at us « . The journalist also cites, among other testimonies on the injustices of the world seen through the press cartoon, Fatou, a Marseillaise:

“In 2015 we still draw black people with big red mouths like Tintin in the Congo, it’s pathetic. But I don’t think it’s to make fun of migrants but rather to denounce what is happening. I don’t think the humor is directed at black people. But, they rather denounce the smugglers: these sellers of the dead. They denounce the inertia of the European and international community. Of course, it might be shocking, but that’s what I see when I look at this drawing. »

This representation by Dilem undoubtedly stands out today as one of the most illustrious denunciations of what is happening in the Mediterranean; as a wake-up call to « put into words » a reality more than a fiction about the daily lives of what are called in the Arab world the « harragas, » the « burners » – in the sense of border burners. Ahmed Ould Djemri Saadaoui, president of the Amicale des Algériens en Europe in Nancy9, who was part of the so-called first generation of French economic immigrants in the 1950s, testifies to the perception of migrants in the news during these crises in the Mediterranean Basin. For his peers, immigration was chosen and desired by countries in need of labor migration. This « sacrificed generation » addressed by the sociologist Abdelmalek Sayad (1999) also contributed to the economy of their country from abroad. In short, with the same determination as contemporary migrants, who are considered outcasts, undesirable but still participating in a cross-Mediterranean economy on both shores. For him, this image of harragas crossing the sea speaks volumes about the societies they come from.

« It is important to notice the contribution of harragas to the awareness of malaise in countries that are rich in resources and rich in motivated youth. These departures are a painful break for the family, but also for the homeland, with a sense of escape, a despair of a youth dreaming of a society optimized by their skills. They no longer dream of it in the face of corruption made ‘legal’ by governments, an all-powerful oligarchy that despises its people by giving them crumbs… Governments even more stuffed by policies and multinationals benefiting from African people and wealth. The departures of harragas show the urgency to rethink so-called democratic systems. »

Political scientist Cherif Dris, in an article on « New Figures of Immigration. In France and in the Mediterranean » (2008), questioned the place of migration issues in Euro-Mediterranean relations by emphasizing the paradoxes of EU immigration policy. Now, the intensification of the fight against illegal immigration turns into a security obsession on one side; the diversion of gray matter from Southern countries on the other. Whether it is called « chosen » or « non-forced » or « concerted » immigration, the risk is the same: keeping these countries in a situation of permanent dependence and underdevelopment. In the end, around the Mediterranean Basin, media interventions on immigration have made waves, and the theme has been taken up internationally. Other countries have used the news and have also experienced media drifts. Therefore, it seems wise to reread the historian Gérard Noiriel already in 1988:

« Of all the old immigration countries, France is the one where immigration flows have always been most closely dependent on the state of the labor market. That is why there is here a stronger link than elsewhere between economic crisis and xenophobia. Indeed, in democratic societies, the essential role of spokespersons is to name the crisis, to designate responsibilities, to propose solutions. Each national society, given its own political traditions, has a ‘stock’ of stereotyped formulas, ready-made explanations, easy scapegoats, which are mobilized to satisfy the electorate and which are found in the political press. »

For Vincent Geisser, a political scientist whose work focuses on the same period as that of Simone Bonnafous previously cited, these types of representations by the press in the 1990s are symptoms of the ethnicization of scapegoats chosen for nationalist political purposes. Thirty years later, following the 2019 European elections, seventy-three far-right MEPs, led by the National Rally and the Italian League, announced the creation of the parliamentary group « Identity and Democracy (ID). » The researchers of the MiMed (Migrations in the Mediterranean) network in Aix-en-Provence, Virginie Baby-Collin, Sophie Bouffier, and Stéphane Mourlane aim to cross disciplines such as history, archaeology, sociology, geography, political science, etc. Their work aligns with the conclusions of interdisciplinary researchers in the fields of Information and Communication Sciences, History, Sociology, and Demography: it makes no sense in terms of history to imagine that we can close borders and live among ourselves. The worldview of everyone at home is certainly not new. Rejection discourses repeat themselves throughout history. Only the populations change when each new generation of migrants is perennially accused of all vices. The repetition in history of these discourses is based on the idea that migrants represent a threat. They are perceived as political enemies, as a source of trouble for society, as unfair competition in the labor market, or even as factors of cultural degeneration. The researchers at MiMed also focus their work on migrations as initiators of synergies leading to the creation of other enriching cultures for both locals and migrants. This again corresponds to the socio-demographic reality that, in addition to integrating individuals into cultures different from their own, there is also the construction of new identities beneficial to everyone. And undoubtedly, the examples observed in the Mediterranean are just a concentrated version of what is happening elsewhere in the world.

Conclusion

If we look back in time, we see that migrations have always brought incomparable wealth with exchanges of cultures and diverse knowledge. The rejection of settled residents, regardless of their origin or geographical heritage, prevails over the acceptance of their quest for well-being. A reflection on the role of the media as a mirror of certain discourses needs to be deepened: despite a very different representation from the reality on the ground, there can be a true distortion of reality that reflects the functioning of the media landscape. Historian Yvan Gastaut and social mediator Bruno Quemada also question in their book « Migrations: when prejudices come into play » (2007), too many prejudices throughout history lead to rejection, exclusion through images conveyed by cinema, the press, extremist lobbies… In this context, undoubtedly, what is the purpose and strength of the law? How can we effectively fight against stigmas? Also, to better understand our present and the complexity of certain phenomena that are thought to be unique when they repeat overwhelmingly, it is necessary to look to the past to advocate for a return to freedom of movement.

Dr. Linda SAADAOUI – PhD. Information and Communication Sciences – Ameddias Luxembourg

Source FR : Colloque ABIDJAN 2019 / AMEDDIAS/CERCOM

——————————————————————————————–

Bibliography

Books

Bonnafous S. (1991). L’immigration prise aux mots : les immigrés dans la presse au tournant des années 80. Paris, France. Éditions Kimé.

Chesnais J.-C. (1981). Histoire de la violence en Occident de 1800 à nos jours. Paris, France : R. Laffont.

Elias N. (1973). La civilisation des mœurs. Paris, France : Calmann-Lévy.

Kalifa D. (1995). L’encre et le sang. Récits de crimes et société à la Belle Époque. Paris, France : Fayard.

Lebon G. (1895). Psychologie des foules. Paris, France. Édition Félix Alcan, 9e édition, 1905.

Lequin Y. (1983). Les villes et l’industrie. L’émergence d’une autre France. Paris, France : Armand Colin

Sayad A. (1999). La Double Absence. Des illusions de l’émigré aux souffrances de l’immigré. Paris, France : Le Seuil, coll. « Liber ».

Noiriel G. (1988). Le creuset français. Histoire de l’immigration, XIXè-XXè siècle. Paris, France : Le Seuil.

Vigarello G. (1998). Histoire du viol XVIe- XXe siècle. Paris, Le seuil.

Contributions de livres

Saadaoui, L. (2009). « Perceptions psycho-sociologiques de l’immigration dans le traitement médiatique du fait divers « tournantes » ». Dans A. Cherqui & P. Hamman (dirs), Production et revendications d’identités, Éléments d’analyse sociologique (p. 117-131). Paris, France : L’Harmattan coll. Logiques sociales.

Sayad A., (1997). « L’immigration et la « pensée d’État ». Réflexions sur la double peine ». Dans S. Palidda (dir.), La construction sociale de la déviance et de la criminalité parmi les immigrés en Europe (p.11-29). Luxembourg, Conseil de l’Europe, COST Migrations.

Articles and Scientific Publications

Dris C. (2008). La question migratoire dans les relations euro-méditerranéennes : entre intégration et obsession sécuritaire. Hommes et migrations, 1266, (3), 126-139.

Gastaut Y., Quemada B. (2007). Migrations : quand les préjugés s’en mêlent. Migrations société, 19, (109), 27-206.

Articles online

Dendoune, N. (2015) « Immigration. Une caricature de Dilem sur les naufragés provoque la colère des internautes », Le Courrier de l’Atlas, 25 avril 2015. Repéré à https://www.lecourrierdelatlas.com/immigration-une-caricature-de-dilem-sur-les-naufrages-provoque-la-colere-des-internautes–2933

Bouffier S., Baby-Collin V. et Mourlane S., « Mister Geopolitix », EchoSciences Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, 13 mai 2019. Repéré à https://orem.hypotheses.org/426

Memories and PhD thesis

Geisser V., Ethnicité et politique dans la France des années 1990 : étude sur les élites politiques issues des migrations maghrébines (Thèse de doctorat). Université Aix-Marseille 3

Saadaoui, L. (2010). Traitements et interventions médiatiques autour des « tournantes » en France : du fait divers à la question de l’immigration ? (Thèse de doctorat). Ecole doctorale Perspectives Interculturelles : Ecrits, Médias, Espaces, Sociétés (PIEMES), Metz-Nancy, en partenariat avec Centre de Recherche sur les Médiations, Metz, France.

Foot notes

- Deciphering rape in our societies is a « grey » figure, that is to say innumerable insofar as even today, many victims do not dare to talk about it. ↩︎

- Initially, La Gazette des tribunaux was intended for an audience of jurists, which it lost at the end of the 19th century to appropriate a readership of curious people, eager for sensationalism. ↩︎

- Refer to the Penal Code, 1810, article 333. It should be noted that the law of 1810 did not give the definition of rape, but only specified that it was punishable by forced labour. It is to the case law (the decisions of the judges) that we must turn to see how this law was applied. Moreover, if La Gazette des Tribunaux regularly mentioned the discovery of news items, it more rarely mentioned the result of the prosecutions. No comment has yet been made on their particularity, even if the code increases the punishment, the « punishment » for their extreme violence ↩︎

- Jean-Marie Le Pen, Élisabeth Guigou and Jean-Guy Talamoni on this occasion discussed the Republic’s values of tolerance on the issue of immigration (09/12/2002). ↩︎

- Ali Dilem published his cartoons in the Algerian daily Liberté, in the television programme Kiosque on TV5 Monde on the French-language channel TV5, and in the French weekly Charlie Hebdo. ↩︎

- In addition, the Italian operation Mare Nostrum had more substantial resources compared to less than a third for Triton. Objectives and a budget that are not without consequences in terms of human resources. Operation Triton, managed by the Frontex agency with the help of 18 states of the Schengen area which provide technical and human resources. The objective of the two operations differs, however. Mare nostrum was clearly displayed as a mission to rescue migrants in distress. Thus, the patrol zone of the Italian navy could move away from its coast to pick up drifting migrant boats, the vast majority of which were in an area close to the Libyan coast. Whereas Triton is above all about protecting the borders of the European Union. This is why the Frontex patrol area is confined to Italian territorial waters, far from the majority of shipwrecks. ↩︎

- The expression « Europe of the Six » refers to all the founding states of the European Union from 1951 to 1973, i.e. Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. ↩︎

- The International League against « Racism and Anti-Semitism », initially named LICA for International League Against « Anti-Semitism », is an association created in 1928 to combat « anti-Semitism ». ↩︎

- Interview of Ahmed Ould Djemri Saadaoui conducted at the Amicale des Algériens en Europe in Nancy, May 26, 2019. ↩︎